Why Do We Enrich Older Americans at the Expense of Everyone Else?

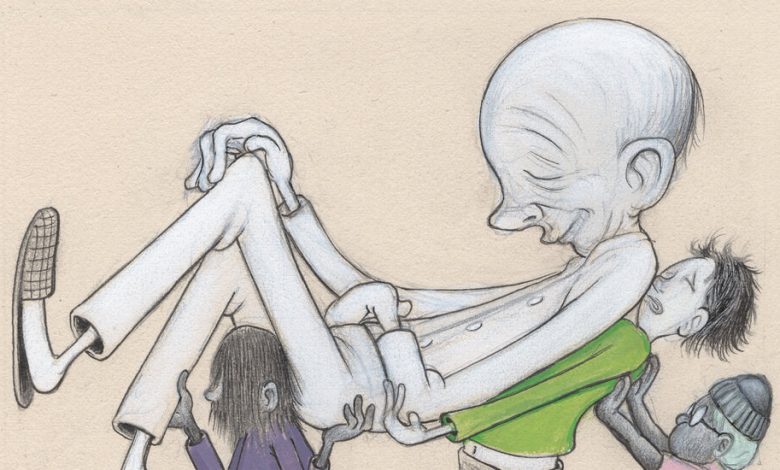

We older Americans are not only controlling national politics, we are consuming an ever larger share of our economy’s resources through programs like Social Security and Medicare, leaving younger Americans to foot growing bills for their parents’ and grandparents’ retirements. And politicians of both parties are refusing to recognize the consequences.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Social Security into law in 1935, the age to qualify for “Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance” was 65. Back then, most of those at that age were poor and lacked health insurance. And many jobs were more physically demanding. When benefits were first paid in 1940, 46 percent of all adult males couldn’t even make it to 65, and for those who did, the average additional life expectancy was less than 13 years. For women, it was not a lot better.

Today, many 65-year-olds are healthy enough to live independently, play golf or pickleball daily and travel far and wide. Picture the vigorous contestants, aged 60 to 75, on the new television dating show “The Golden Bachelor.” Every contestant older than 70 is retired, as are some as young as 60. “Here’s to Social Security!” one grateful contestant exults. Indeed!

For a typical 65-year-old couple, at least one partner, on average, will likely make it to 90 or beyond. Yet even as life expectancy has risen since 1935, the minimum age to qualify for at least a portion of your Social Security benefits has fallen to 62. That means that many people are now drawing from Social Security for as much as a third of their adult lives, if not more. If people took the same number of retirement years as the average person retiring in 1940, they would stop working at around 77. As such, Social Security is increasingly losing its purpose as old-age insurance, as benefits stretch well into what is becoming late middle age for many.

With Medicare and Social Security, older Americans are taking far more out of the system than they paid in. Consider how much lifetime Social Security and Medicare benefits have grown. For a typical 65-year-old couple, those benefits, adjusted for inflation, are worth over $1.1 million today, compared with $330,000 in 1960. Benefits rise as each generation lives longer and receives amounts that grow with the cost-of-living, and as medical prices rise and expensive medical treatments proliferate. Yet the lifetime taxes this couple pays into Social Security and Medicare amount to about $650,000.

And the number of people available to pay for each retiree’s benefits is dwindling: Declines in birthrates and, at times, immigration rates, have helped lower the ratio of covered workers to beneficiaries, from 4.0 in 1965 to 2.7 today, with 2.3 projected in two decades.

The young have been losing out for some time: 80 percent of federal spending growth since 1980 has gone to Social Security and health care (much of it for Medicare), according to Mr. Steuerle’s calculations. That growth has been paid for with taxes, additional borrowing and cuts in other programs — the latter two disproportionately affecting those still working.

Nearly everyone in Washington, Democrat and Republican, socialist or MAGA, is aware that withdrawals from these programs exceed the money being put in. They are just too scared to do anything about it. Just look at the budget compromise earlier this year. Like many past ones, it protects the growth of Social Security and Medicare — and cuts the share of the budget devoted to discretionary programs like science and research, environment and education. The only thing to be resolved in the budget battle that threatens another government shutdown is how much further to limit growth in these other programs.

To start devoting a reasonable share of resources to everything from better education to reform of student loans to addressing climate change, we must redefine “old age” to reflect that most Americans are living longer and better lives than they did in the mid-20th century. We must adjust our retirement expectations and the government and private programs that largely define them.

To sustain the government’s two biggest entitlement programs, taxes must be increased — with the wealthy paying a fair share, some would argue — or benefits cut, or both, many analysts agree. But there’s another way to help long-term: Those in late middle age will need to work longer as they live longer. That would help shore up revenue with additional Social Security taxes and the income taxes that largely pay for Part B of Medicare. It would also reduce pressure to cut benefits for the oldest of the old.

We can adjust Social Security to help achieve that goal. We can both increase revenues and reduce spending by increasing the earliest retirement age from 62, and also the full-retirement age from 67. (The most recent increase, from 65, was approved 40 years ago.)

We acknowledge the unpopularity of this idea — look at protests in countries like France and Russia when they did this. But some minds might be changed by noting that the big winners from growing retirement support are richer Americans, who tend to live longer.

Medicare, which effectively discourages work after 64, also needs to be redesigned. We believe that a worker eligible for Medicare should be allowed to take it in lieu of employer insurance, and negotiate with an employer for cash compensation. Then we need to address myriad other distortions. In traditional employer pension plans, which still dominate state and local government, a worker can lose huge benefits by working beyond full retirement age.

By saving money on those who don’t need it, we can also reorient spending toward those who actually do. We’re not asking a laborer or trucker who did backbreaking work for decades to keep working. Congress could enact a more liberal definition of disability for such workers who reach 60. A strong minimum benefit could essentially eliminate poverty among the elderly.

Social Security could also encourage people to delay full retirement by adding more flexibility and transparency to the existing deferral process. This could mean allowing seniors to defer a different share of benefits each year after the early-retirement age and the full-retirement age, according to their needs, health and part- or full-time jobs. The benefits they defer would be credited toward a higher benefit later.

State tax systems also offer subsidies to seniors unrelated to needs. As noted by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “the median state asks senior citizens to pay about one-third less in personal income tax than younger families with similar incomes.” Income from private pensions, for instance, is fully exempt from taxes in four states, and partly exempt in more than a dozen others.

As the programs that support us older Americans put ever greater pressure on working families, is it asking too much to encourage everyone, old and young, to embrace a future where our healthiest and wealthiest take a little less and contribute a little more? By the way, research shows emotional and cognitive benefits to working and volunteering.

Younger Americans must help lead this transformation because every year reform is delayed, they and future generations will receive less support during their working and child-raising years. Just as their parents and grandparents did on important issues, it’s time for them to speak out and step up.

C. Eugene Steuerle is a former Treasury official who co-founded the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center; Glenn Kramon is a former New York Times editor now lecturing at Stanford Business School. Both are in their 70s.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.