Inside the Making of New York City’s Bizarre Nuclear War P.S.A.

The video opens gauzily on an empty New York City streetscape, with sirens echoing in the distance, as a woman dressed in black strolls in with some hypothetically catastrophic news.

“So there’s been a nuclear attack,” she says nonchalantly. “Don’t ask me how or why, just know that the big one has hit.”

The 90-second public service announcement, which instructed New Yorkers about what to do during a nuclear attack, was released by the city’s Department of Emergency Management in July.

It attracted attention: While most of the videos on the department’s YouTube page have recorded fewer than 1,000 views, at last count the nuclear preparedness video had been seen more than 857,000 times.

It also drew immediate and widespread derision, much of it centered on an underlying question: What were they thinking?

Mayor Eric Adams and other city officials were peppered with more specific questions. Who greenlighted the video? Why did the city release it now? Did the city know of a potential nuclear threat, and was this how it was warning New Yorkers? And was the advice — “Get inside. Fast.” — even useful?

In response, Mayor Adams defended the video, saying he was a “big believer in better safe than sorry.” But city officials have said little else about the video, from its origins to the reasoning behind its release, though officials did quickly clarify that they had no reason to believe any sort of attack was imminent.

In interviews with current and former city officials, radiological emergency experts and a Brooklyn-based video and sound production company, a clearer picture began to emerge of how the video came to be. Some of the answers lay behind the doors of the company hired by the city to produce it, but even there, mystery and misdirection awaited.

The city’s Emergency Management agency is headquartered in a $50 million command center in Downtown Brooklyn, built after its former office was destroyed on Sept. 11. Part of its mission is to inform the public of best emergency preparedness practices, and one way it does so is through public service announcements.

Many of the videos are made by an outside contractor, Splash Studios, which has a $400,000 contract to provide the department with videos over four years.

The studio’s work for the city has covered topics like coastal storms and ranked-choice voting. Among its other work is a video for Scientific American about Cesar Millan, a man known as the “Dog Whisperer.”

The firm claims its success helped it move from a “small office located within another business to a 5,000-square-foot facility,” according to its LinkedIn profile. But a man working at the front desk at that building, on West 23rd Street in Manhattan, said he had not heard of the company and it had not been a recent tenant.

At some point in December 2018, the studio began work on a new video for the city that was very much unlike its other work, either in tone, context or look.

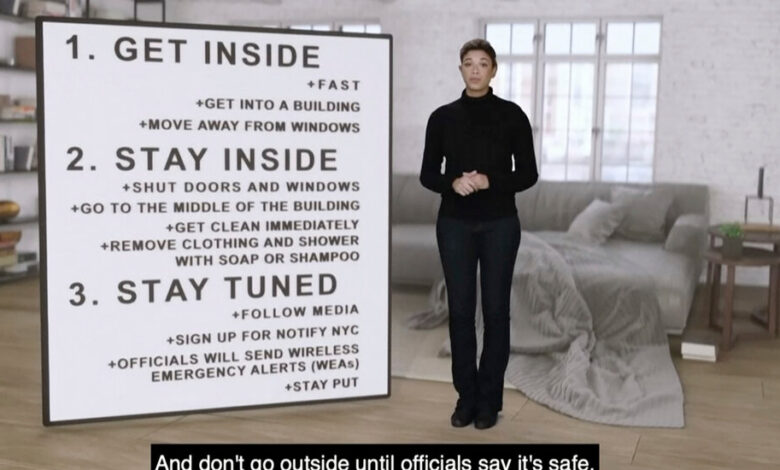

After the woman in the video has delivered the news that “the big one has hit,” she is next seen inside a spacious apartment with an exposed beam ceiling and a wide brick wall. She advises New Yorkers to go indoors, to avoid seeking shelter in automobiles and to stay tuned for more information.

Donell Harvin, a senior research scientist at the RAND Corporation who studies weapons of mass destruction, and the former head of the city’s radiological emergency response unit for the Department of Health, called the announcement reckless and “a fabulous waste” of taxpayer money.

“People weren’t asking about what to do in a nuclear device scenario. They’re living with day-to-day crime in New York,” said Mr. Harvin, who helped write the city’s radiation response plan in 2008. “It just makes it look like an unstable, out-of-control world that we live in.”

The company’s owner, Barbara Parks, did not initially return repeated requests for comment. A reporter recently rang the bell at her apartment in the Fort Greene neighborhood of Brooklyn.

The woman did not come to the door, and Ms. Parks later sent a text message: “Sorry. Running late. Please email.”

Ms. Parks confirmed in an email the next day that her company produced the video. Asked about its unusual style and tone, Ms. Parks said only that she was asked by the city to “use a live-action presenter in a digital environment.”

She did not respond to follow up emails.

Emergency Management officials were also somewhat elusive in providing information about the video. They initially said that the city began working on the project in late 2019, shortly before the coronavirus pandemic hit the city.

“We postponed the release of the video to focus on the public health emergency,” a spokeswoman for the agency said in a statement. The spokeswoman eventually acknowledged that officials began working on the project in 2018, well before the virus reached New York.

The Times reached Joseph Esposito, then the Office of Emergency Management commissioner. He said the idea for the nuclear preparedness video came out of a brainstorming meeting.

“Back in 2018, we started talking about this,” he said. “I said OK, give me your ideas on it. I got fired, and I never followed up on it.”

Mr. Esposito said in an interview that he had seen the criticism of the video, but said that the city was right to educate the public about different types of emergencies.

Splash Studios delivered the video to the city in January 2019. Then it gathered dust for three and a half years before its release this summer.

The city’s new emergency management commissioner, Zachary Iscol, declined to answer questions about the video; his press team acknowledged only that Mr. Iscol had seen it before approving its release.

Mr. Adams said in a news conference that he, too, had seen the video before its release and authorized its distribution.

Mr. Adams, who has his own history with a viral video — as a state senator, he demonstrated how parents could check their children’s dolls for drugs — said that the nuclear preparedness video was scheduled “after the attacks in the Ukraine, and O.E.M. took a very proactive step to say, let’s be prepared.”

“When I saw it and heard it, I thought it was a great idea,” Mr. Adams told reporters.

Many Americans are concerned about the prospect of a nuclear attack. Nearly 70 percent of residents said they were “worried the invasion of Ukraine is going to lead to nuclear war,” according to a survey in March by the American Psychological Association.

Still, some questioned whether the city should have prioritized the nuclear preparedness video at a time when emergency officials are grappling with more imminent threats, like extreme heat and catastrophic flooding, and the city is dealing with the monkeypox health crisis.

Mr. Harvin, the former city official, said that emergency management professionals traditionally focus on events that are more likely to occur, including flash floods or mass shootings. New York City has recently experienced both.

The city’s 2019 “Risk Landscape” guide to the hazards facing New Yorkers focused on climate change, and a nuclear attack was the last item to be addressed in the guide, preceded by coastal erosion, storms, earthquakes, extreme heat and flooding.

FEMA officials were made aware of the public service advertisement before it aired. While the agency “has not determined a specific nuclear threat” to New York City, agency officials said they deferred to the city to discuss the threat environment and any “intended or unintended results of the messaging campaign.”

The federal agency’s current administrator, Deanne Criswell, had previously served as head of New York City’s emergency management, succeeding Mr. Esposito in July 2019. Jeremy M. Edwards, a spokesman for Ms. Criswell, said that discussions about the nuclear attack video predated her time as commissioner and were resurrected after her tenure ended.

“While serving as commissioner, Administrator Criswell was largely focused on helping the city respond to the Covid-19 pandemic,” Mr. Edwards said.

City officials have made clear that the city was not at a heightened risk. Christina Farrell, a first deputy commissioner at Emergency Management, said in an interview that a nuclear attack was a “very low probability event, but with potential high impact.”

The video was a success, Ms. Farrell said, because it got people’s attention. Her department’s other videos about flood zones and extreme heat are often ignored, and a recent one on “Packing Your Go Bag” has been viewed fewer than 250 times since it premiered in September.

“We’re happy when people are thinking about emergency preparedness,” Ms. Farrell said.

But three emergency management experts interviewed by The Times said the way the advertisement was released in a vacuum and seemingly without notice was flawed. Alarming public service announcements are normally preceded by a notice to the public that an educational campaign is on the way.

Joann Ariola, a councilwoman from Queens and chairwoman of the Committee on Fire and Emergency Management, said she heard concerns from some of her constituents who were alarmed by the video, but she explained that it was designed to address their anxieties.

“The whole reason for the outreach is to find out what people are thinking and to try and help calm their fears in knowing that these are steps you can take in case an incident occurs,” Ms. Ariola said.

The city’s advice on nuclear attacks — to go inside and await further information — matches federal recommendations. The Department of Homeland Security website offers similar tips to “prevent significant radiation exposure.”

While the advice is sound and will protect those not in the blast radius from nuclear fallout, Mr. Harvin said it lacks context. When he worked for the health department, they studied models for what would happen if New York City was struck by “the big one,” a powerful, modern-day nuclear device.

“Game over, baby,” Mr. Harvin said. “There’s no going into your house and closing your doors because the house is gone.”