Fall for Dance Review: Some Tap, a Pas de Deux and a Monastic Chorus

With its something-for-everyone ethos, the Fall for Dance festival, nearly 20 years old, continues to pack the house at New York City Center and two-plus years of a pandemic have made no discernible dent in its popularity.

On opening night last Wednesday, the line to enter the theater snaked around the block from 55th Street onto 7th Avenue. That enthusiasm was also evident inside, where the warmly received Program 1 featured Compagnie Hervé Koubi from France, a teenage duo from the Bavarian State Ballet and New York City’s own Gibney Company.

Ideally, Fall for Dance is a place of happy discovery, where viewers are introduced to something they haven’t seen before and will want to seek out again. Of this year’s first two sample-platter programs, it was the second, for me, that offered this kind of encounter — most notably with Music from the Sole, a tap dance and live music company led by the choreographer-composer team Leonardo Sandoval and Gregory Richardson. An unforced crowd-pleaser, original and true to itself, their “I Didn’t Come to Stay,” which shared a program on Friday with a Pam Tanowitz duet and Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, was Fall for Dance at is finest.

The curtain rose on a colorful ensemble already in motion, as if mid-celebration, singing and processing across the stage. While different roles would soon emerge, as members of the group peeled off to play various instruments or stayed dancing center-stage, this sense of togetherness and collective joy extended throughout the work.

On his website, Sandoval, who is from Brazil and works in New York City, describes Music from the Sole as exploring “tap dance’s Afro-diasporic roots and lineage to a wide range of Black dance and music,” citing jazz, samba, house and passinho (Brazilian funk). In “I Didn’t Come to Stay,” these influences seamlessly intertwine, showing the artists’ easy command of their wide palette.

A section of precise a cappella tapping and body percussion — with some performers in tap shoes, others in sneakers — flows into a barefoot, samba-infused dance, punctuated by a playful hip-shaking interlude. Sandoval himself, with his lanky physique and affable presence, sails through a lithe, fluid tap solo. Later, in an electrifying duet with Gisele Silva, they stamp out a beat as the foundation for further rhythmic layering. Structured but loose, the work has an appealing roughness and relaxed energy, its performers like friends at a party.

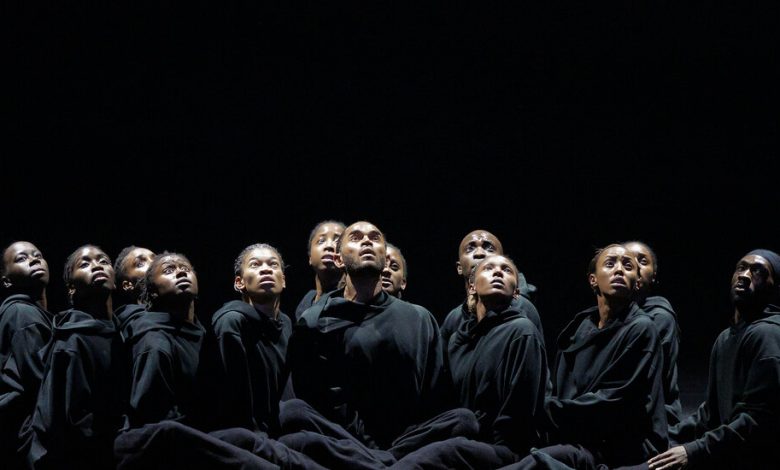

At Fall for Dance, an imperative to entertain sometimes outweighs everything else. Such was the case with Aszure Barton’s 2009 “Busk,” gorgeously danced by 13 members of the Ailey company, who form a kind of monastic chorus, draped in black clothing (blazers over hoodies over pants). While visually stimulating and full of technical feats, this work’s deeper motivation remains as opaque as the costumes. Regardless, it’s a vehicle for some striking performances, in particular Jacquelin Harris’s hyper-focused solo beneath a disco ball, in which impulses ripple through her body with laserlike clarity and speed.

Sandwiched between the two ensemble numbers on Program 2 was an idiosyncratic whisper of a duet, “No Nonsense,” by Pam Tanowitz, for Melissa Toogood — a longtime Tanowitz dancer — and Herman Cornejo of American Ballet Theater. Matching outfits of fuzzy pink shirts and shorts, designed by Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung, helped bring these two stars down to earth, as did the humanity in Tanowitz’s choreography.

Intimate gestures — one dancer’s foot grazing the other’s calf — caught the eye as much as Toogood’s swerves of the torso or Cornejo’s lucid leaps. The vocalists Kate Davis and Katie Geissinger, seated on the floor, provided the music, which progressed from the fragmentary intonations of Meredith Monk’s “Walking Song” to Peter Sarstedt’s “Where Do You Go To My Lovely.” The transition from breathy syllables to a song with lyrics, awkward at first, later seemed to echo the dancers’ relationship, with its tensions between tentative and boldly trusting.

Program 1 had fewer surprises. In excerpts from “Boys Don’t Cry” (2018), the strapping men of Compagnie Hervé Koubi told childhood stories of being pressured to act in typically masculine ways: to play sports, to fight, to not cry. They paired these, a bit haphazardly, with their signature acrobatic (and shirtless) dance moves, a blend of styles like breaking and capoeira.

In a display that my date aptly called “Instagram IRL,” Margarita Fernandes and António Casalinho — teenage dancers from the Bavarian State Ballet, who have about 50,000 Instagram followers combined — nailed every step in a pas de deux from “Le Corsaire.” Impeccable but mechanical, they danced as if posing for a camera or for the watchful eyes of competition judges — understandably given their training so far. They have plenty of time to grow.

The Gibney Company closed Program 1 with the North American premiere of “Bliss,” by the Swedish choreographer John Inger. In this sweeping ensemble work for 13 dancers, the continuity of the dancing mirrors that of the jazz piano soundtrack by Keith Jarrett. It amounts to a lot of lovely material, beautifully presented, without a driving force. Why are these people dancing together? What for? In some works, like Music from the Sole’s, that’s never a question.

Fall for Dance

Through Oct. 2 at New York City Center; nycitycenter.org.