Review: The Inescapable Vibrations of ‘Violet’

The lights go up on five dancers standing at the back of the stage, evenly spaced, facing outward. It’s the configuration of a police lineup or of the audition scene in “A Chorus Line.” But this is “Violet,” by the American-born, Europe-based choreographer Meg Stuart, and for a long while no one moves at all.

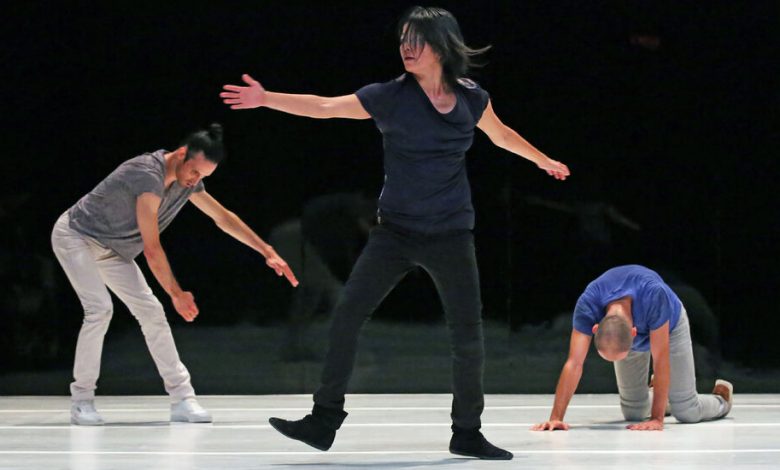

The hands of one dancer begin to pulse, the torso of another to rotate. Arms go into action but not feet, which remain planted. Each dancer moves with intriguing, individuating specificity: this one shaking, that one twitching sinuously or twisting like the head of a sprinkler. Yet all this oscillation seems to be in response to some common signal.

At New York University’s Skirball Center for the Performing Arts, where “Violet” had its United States premiere this weekend, we can see, hear and even feel the source: the musician Brendan Dougherty onstage with laptop, electric guitar and drum kit. Starting with the sound of surf, he methodically layers more cyclical sounds in waves, adding and subtracting alarms, distortion, chopping vibrations like those of helicopter rotors, low frequencies that resonate in your chest. He’s the conductor of energy.

As that energy slowly builds and the volume rises, you wonder how the dancers will respond. Will those feet ever come unstuck? They do. The dancers stumble, spin, fall, roll. They sink onto all fours or splay prone, still shaking. Will they ever interact? Sort of. Synchronicity appears in flashes, collectivity in drift.

Where can all this rising action go? It can stop. When Dougherty kills the noise, the silence resounds, and the dancers return to stillness, in a line again, now at the lip of the stage. But the electricity is still flowing — we can hear the static — and the tremors start again.

It is around this point that the 75-minute work begins to feel overextended and slack. Made in 2011, it also feels like a signal that’s taken a bit too long to arrive, reminiscent of other works from that time and no longer fresh or in fashion. Although less theatrical than many of the other pieces Stuart has made with her company, Damaged Goods, it is similarly smitten with failure — here, with false hints, false endings. Does it matter when the dancers turn back and see themselves in the reflective rear wall or when they finally make contact with one another in fleeting, impersonal touch? Not really.

It’s a vision I found disappointing. The hard-rock maelstrom that the music seems to promise never quite arrives. In the language of “Spinal Tap,” the dancers, though committed, never go to 11; it’s regular violet, not ultra. Instead, the big moment comes when two of them, rolling over each other, slowly gather in the others like a tumbleweed. They’re doing with their bodies something like what Dougherty was doing with sound, but it’s much more predictable.

And that’s not the end. Again, they rise and plant their feet and register the vibrations. The lights slowly fade, as if in resignation.

“Violet”

Performed Sept. 23 and 24 at New York University’s Skirball Center for the Performing Arts.