Mills Lane, Who Refereed Tyson Ear Bite Fight, Dies at 85

Mills Lane, a former district attorney and judge who became one of boxing’s most prominent referees, overseeing more than 100 championship bouts and delivering his exuberant catchphrase — “Let’s get it on!” — before the first round began, died on Tuesday at his home in Reno, Nev. He was 85.

His son Terry said the cause was complications of a stroke he had in 2002, which left him unable to speak.

Mr. Lane, a former amateur and professional boxer, was known for his take-charge style in bouts between many of boxing’s elite champions, including Muhammad Ali, Larry Holmes, Roberto Durán, Marvelous Marvin Hagler and Thomas Hearns.

Despite his small stature — he stood 5 feet 7 inches tall and weighed about 150 pounds — he exerted a strong sense of command in the ring, much as he did in his legal career in Washoe County, where Reno is the county seat. As a prosecutor, he was called “Maximum Mills,” for the long sentences he was able to secure against defendants.

“He was one of the most respected referees in the world,” Marc Ratner, the former executive director of the Nevada State Athletic Commission, said in a phone interview. “And when he got in the ring fighters knew there was a special quality about him. He was a man’s man.”

But almost anything can happen in boxing, and Mr. Lane witnessed his fair share of unusual moments.

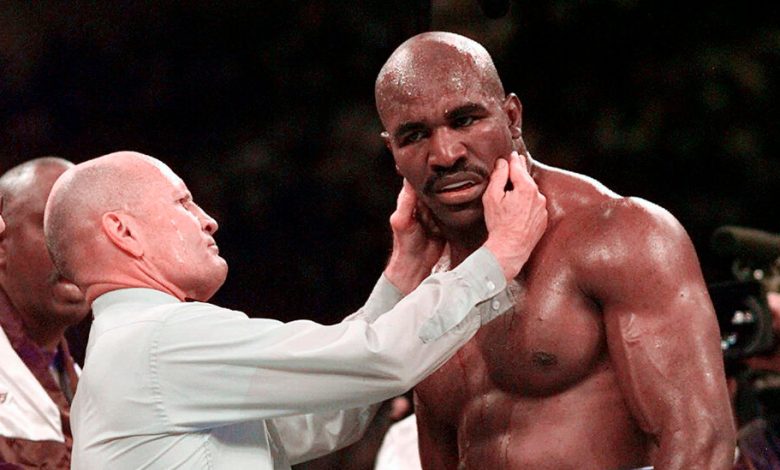

The rematch in 1997 between Mike Tyson and Evander Holyfield for the heavyweight championship became a bloody spectacle when Tyson, enraged at being headbutted by Holyfield in the second round, bit off a piece of Holyfield’s right ear and spit it to the mat during the third.

“He bit him!” Mr. Lane shouted. “He’s disqualified!” But after consulting with Mr. Ratner, who asked him if he was absolutely certain that he wanted to eject him, he chose instead to deduct two points from Tyson for the grotesque foul. And when the ringside doctor affirmed that Holyfield could continue, the fight went on — until later in the round when Tyson chomped on Holyfield’s left ear, which prompted Mr. Lane to disqualify him for good.

“One bite is bad enough,” he said after the fight. “Two bites is not deserved.”

In 1997, he disqualified Oliver McCall when he appeared to be having a nervous breakdown during his heavyweight title fight against Lennox Lewis.

“It was almost as if he wanted to get knocked out,” Mr. Lane said after the bout. “He wasn’t putting up any semblance of a defense, so I figured that was it.”

He also disqualified Henry Akinwande in a fight that year against Lewis for excessive clinching and holding.

And in 1998, Mr. Lane accidentally pushed the middleweight champion Bernard Hopkins through the ropes when he tried to break up the headlock that Robert Allen was holding Hopkins in. Hopkins was injured, and the fight was declared a no contest.

“It was just one of those things that happen,” Mr. Lane said after the fight, one of his last.

Mills Bee Lane III was born on Nov. 12, 1937, in Savannah, Ga. His father, Remer, moved his family after World War II to a plantation in South Carolina where he raised cattle. His mother, Louise (Harris) Lane, was a homemaker. Remer chose not to enter the family-owned business, the Citizens and Southern Bank, as did young Mills.

He listened to boxing on the radio and, after graduating from boarding school, joined the Marines in 1956, where he learned to box. While he was stationed in Okinawa, he won the Marines’s All-Far East welterweight championship. Determined to continue as a boxer, he enrolled at the University of Nevada, Reno, and won the 1960 N.C.A.A. welterweight title.

Although he failed to make the 1960 Olympic team, he soon turned professional. He lost his first fight but won the next 10 (one of which avenged his loss) before retiring in 1967, knowing he didn’t have enough talent to be a champion.

By then, he had graduated in 1963 from the University of Nevada with a degree in business and began refereeing. He got his law degree from the University of Utah in 1970.

After working in a law firm for two years, he was hired as a Washoe County prosecutor and elected district attorney in 1982. “Having Mills in the courtroom as a prosecutor was a challenge,” Charles McGee, a district court judge, told The Reno Gazette-Journal in 1998. “There was always this question about who was going to run the courtroom.”

Mr. Lane was elected a district court judge in 1990.

He carried a gun to defend himself if any of the people he sent to the state penitentiary got out and came after him. “It goes everywhere I go, brother,” he told a New York Times reporter in 1997. “Except on the airplanes.”

He added, “I’ve got two darling sons, Tommy and Terry. If somebody was to come to my home and hurt my boys intentionally, I’d have a tag on their toes before the sun goes down.”

In 1998, he made several changes to his career. He retired from refereeing, stepped down from the bench after nearly two terms to go into private practice, and began his starring role in the syndicated TV series “Judge Mills Lane,” an opportunity that came to him because of the sudden national renown that came from the Tyson bite fight.

“The producers learned he was a real judge and made him an offer he couldn’t refuse,” Terry Lane said in a phone interview. “In one year, he went from overseeing murder trials to ‘this person owes me money for a dog.’”

The series was canceled in 2001, and Mr. Lane had his debilitating stroke a year later.

In 2013, he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

In addition to his son Terry, Mr. Lane is survived by his other son, Tommy; his wife, Kaye (Pearce) Lane; his sister, Louise Talbot; and his brothers, Remer and Tom. Two previous marriages ended in divorce.

An hour before the Tyson-Holyfield fight, a memorabilia collector from Canada offered Mr. Lane $200 for the blue shirt that he would wear in the ring.

“Hey man, one more thing,” Mr. Lane said he told the man when he recounted the story for The Times. “It’s probably gonna be a dirty shirt after this is over.”

“Don’t care,” the man said. “I want the blood and all.”

“OK,” Mr. Lane said. “The blood and all.”

He sold it and, because of the notoriety of the fight, had some regrets.

“What I should’ve done was hold my shirt up and start the bidding at $200,” Mr. Lane said. “I could’ve probably gotten $4,000 for it, but, oh well, I’d given the man my word.”