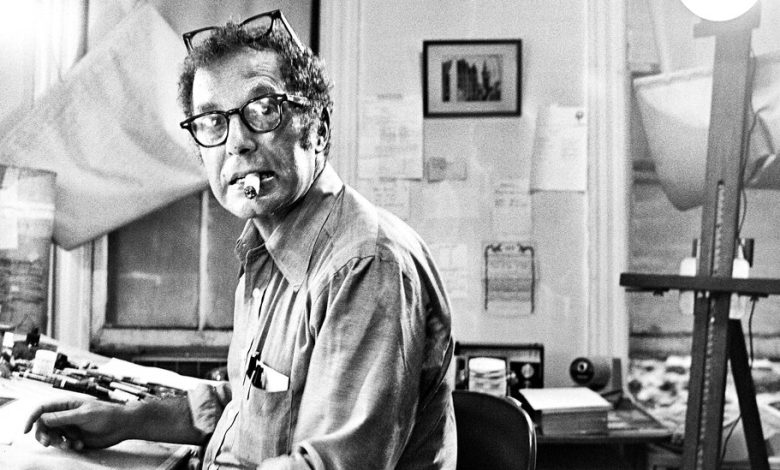

Sam Gross, 89, Dies; Prolific Purveyor of Cartoons, Tasteful and Otherwise

Sam Gross, whose cartoons wrenched gags from frogs’ legs, fairy tales, cats, aliens and cave men, drawing belly laughs whether they graced the pages of The New Yorker or eviscerated notions of taste in National Lampoon, died on Saturday at his home in Manhattan. He was 89.

The cause was complications of heart failure, said Pat Giles, a co-executor of his estate.

Mr. Gross was prolific; even near the end of his life, Mr. Giles said, he drew up to 17 ideas for cartoons a week, and his lifetime total was more than 33,800 rough and completed cartoons. In addition to The New Yorker and National Lampoon, he sold his work to Esquire, Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, greeting card companies and mildly pornographic men’s magazines. His adaptability, he said, was a key to his longevity.

“I was never part of any scene except my scene,” Mr. Gross said in a 2011 interview with The Comics Journal. “Which is one reason I survived.”

As a New Yorker cartoonist, Mr. Gross was widely ranked among giants like Charles Addams and Saul Steinberg, as well as more contemporary stars like Roz Chast. Bob Mankoff, The New Yorker’s former cartoon editor, who worked with Mr. Gross for many decades, said in a phone interview that he was “in the pantheon,” adding, “No one has ever done funnier cartoons than Sam Gross.”

As a National Lampoon cartoonist, starting in 1970, and, for some years, the magazine’s cartoon editor, Mr. Gross joined forces with artists like Gahan Wilson (who, like Mr. Gross, also flourished at The New Yorker) and Rick Meyerowitz to create humor in which everything, from race to sex to disabilities, was fair game for a gag.

And while there are lines of taste that many cartoonists will not cross, Mr. Gross leaped over them, doused them with gasoline and lit them on fire, cackling as he did.

A stiff-legged dog lies on its back next to a blind man holding a sign that says, “I am blind, and my dog is dead.” A gigantic beanstalk grows out of a medieval peasant’s posterior, and another peasant says, “I told you they were magic beans and not to eat them.” Diners sit in front of a sign advertising frogs’ legs in a restaurant as a despondent legless amphibian rolls out of the kitchen. Some of his cartoons can’t be fully described in a family newspaper.

“Sam was so fantastically profane,” Mr. Meyerowitz, the author of “Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead” (2010), a colorful history of the Lampoon, said in a phone interview. Mr. Gross, he added, “resented people saying, ‘Oh, you can’t say that,’ when he knew he could.”

But the point for Mr. Gross was not simply to shock people but to make them laugh. “He didn’t seek to offend,” Mr. Mankoff said. “but the goal of a cartoon should never be that it shouldn’t offend.”

His cartoons delighted readers even when they dealt with less grotesque or taboo subjects.

A smiling cat pulls a mouse in a toy car. Another mouse shouts “For God’s sake, think! Why is he being so nice to you?”

A cow jumps over the moon. Another cow watching from a field says to a calf, “Son, your mother is a remarkable woman.”

Mr. Gross’s first New Yorker cartoon, which showed a woman staring at a boy chasing a windup bus past her bus stop, was published in 1969; his last appeared in February. He published more than 400 cartoons there during the more than five decades in between.

Mr. Gross had less of an immediately identifiable visual style than George Booth’s kinetic lines or Edward Koren’s shaggy drawings. (Mr. Booth and Mr. Koren, his fellow star cartoonists at The New Yorker, died within the past few months; Bruce McCall, a satirical artist whose work appeared in both The New Yorker and National Lampoon, died last Friday.)

Mr. Gross’s drawing style consisted of elegant simplicity in service of the joke.

In an obituary for The New Yorker, Emma Allen, the magazine’s current cartoon editor, called his work “a tightrope walk of economy — precariously achieving maximum hilarity in the fewest moves.”

A man at a gathering opens the door to the grim reaper and says, “I do hope you’re here for the circumcision.”

Two witches stir a bubbling cauldron. One says “I’m writing a memoir. It’s mostly recipes.”

Mr. Gross, who spoke with a rasping Bronx accent and had a slight stoop from decades spent hunched over the drawing board, was a mentor to, and advocate for, other cartoonists, quick to emphatically point out what he saw as injustices in the cartooning business. Mr. Meyerowitz said he pushed for royalty payments for cartoonists; Mr. Mankoff said he refused to sell cartoons to outlets, like Playboy, that completely controlled the rights to them.

In addition, Mr. Gross said that he never changed his style just to sell cartoons.

“My work hasn’t changed because of The New Yorker,” he said in 2011. “I don’t do things for The New Yorker; I do things for me.”

Samuel Harry Gross was born in the Bronx on Aug. 7, 1933, to Max and Sophie (Goldberg) Gross, Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. His father was an accountant, his mother a homemaker.

After attending DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, he graduated from the City College of New York, where he studied business, accounting and advertising.

Mr. Gross told The Comics Journal that his first published cartoon ran in Saturday Review in 1953, and that his first book of cartoons, “Cartoons for the GI,” was published after he was drafted into the Army in 1954.

His other books of cartoons include “I Am Blind, and My Dog Is Dead” (1977), “More Gross” (1982) and “We Have Ways of Making You Laugh: 120 Funny Swastika Cartoons” (2008). His frog-legs cartoon appeared on the covers of the 1977 National Lampoon comedy album “That’s Not Funny, That’s Sick!” and the program for the touring stage show that followed.

After serving in Germany for two years, Mr. Gross moved back to the United States. He briefly worked as an accountant and saved his money, and in 1959 he married Isabelle Jaffe. She survives him, as do their daughter, Michelle Gross, and a sister, Sarita Abrahams.

After they married, the Grosses moved to Darmstadt, Germany, near Frankfurt, where Mr. Gross sold cartoons to European publications. After about a year they moved back to New York, where Mr. Gross submitted cartoons to The New Yorker and The Saturday Evening Post, as well as less respectable magazines like Rascal. By the early 1960s he was able to make a full-time living as a cartoonist.

Mr. Gross was a meticulous record keeper, which he attributed to his accounting background. He kept all his cartoons, numbered and ordered in large black binders, with copies sorted by topic, in a studio on the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

He was also outspoken, and he let people know when he disagreed with them. Mr. Mankoff said that Mr. Gross flatly refused to participate in The New Yorker’s caption contest, in which readers contribute caption ideas for a cartoon:

“He basically said, ‘If you’re not going to let somebody write the last paragraph to an Updike article, you’re not doing anything to my caption.’”